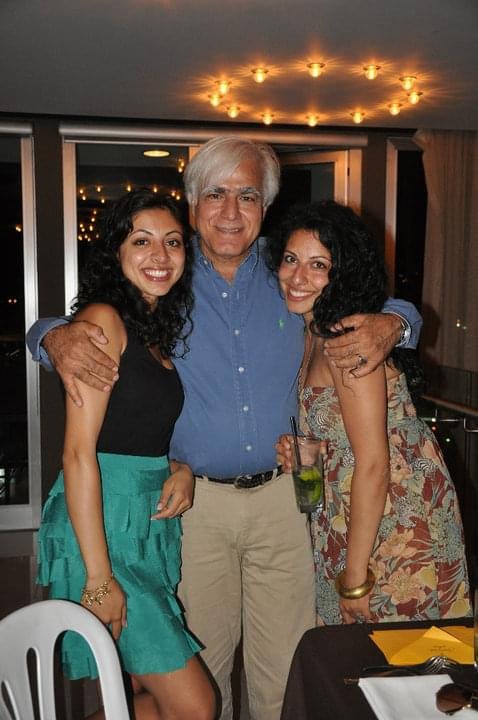

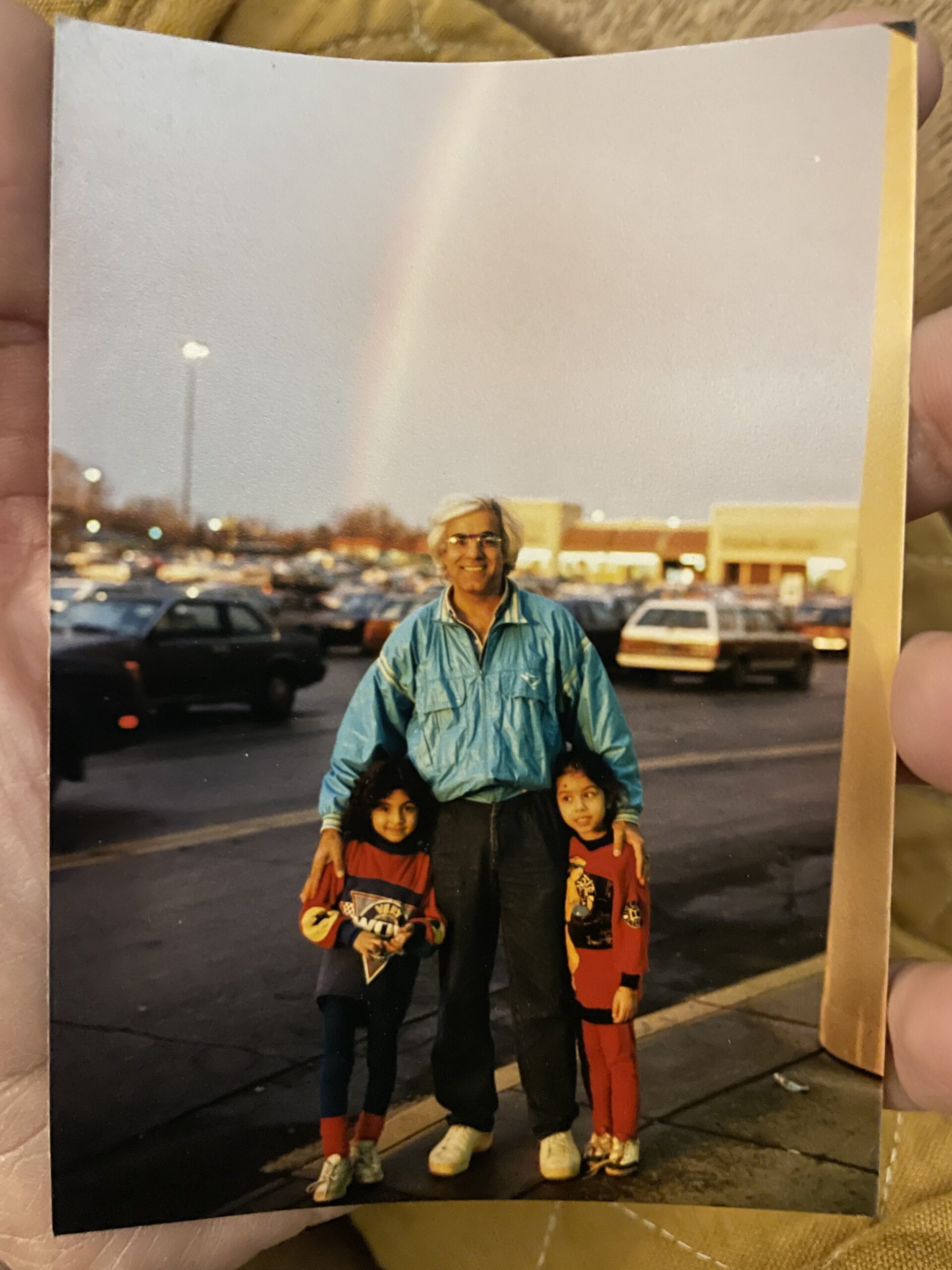

I slow myself at the bathroom sink, turning water over my hands, marveling at the feel of liquid slipping through my fingers. That glorious water. I savor the soap too. I slow down my breath when I’m outside, taking great big inhales and exhaling equally long. I have been doing these small pleasurable things, these tiny acts of ritual or even eroticism, because Afi and Uncle Hamid don’t get to feel anymore.

In less than a year, my family lost two of its brightest, most vibrant members, one to a ferocious and quick cancer; the other in sleep to cardiac arrest. Both were too soon. I still toy with denial, texting my cousin “For real they’re gone?” at least twice weekly. These are the people who raised me. These are the people who shaped who I am. And though I wrote this piece before the massacre at Robb Elementary in Uvalde Texas, the entirety holds true: grief rendered fresh. Grief: consistent, unfathomable. I am a mother of four young kids; all I can think about are those mamas. Those caregivers. Everyone who loved these children, and their two beautiful teachers.

So how many days are we given to grieve?

Some folks seem to understand, in meetings, in classrooms. There’s the automatic frown and “I’m so sorrys,” which feel at times like a balm and other times like lip service, so often followed by next steps and must dos that signal the emptiness of cookie cutter words. After all, we are “professionals,” right?

How many educators try like I do sometimes, despite the suffering and pain, to appear strong? Is that even strength, burying emotion and hardship without recognition and healing? What message does it send our children, that we don’t “fall apart” in the face of consistent loss? And in what ways can I show instead a graceful manner of naming how I feel, what I need to heal, and how grief affects me still?

This conversation is about humanity.

Because matters of eternity have no timeline.

We have all been hurting so much. We’re expected to bury our dead and bury our grief just as quickly, no matter how sudden, how horrific, how traumatizing. Our children are watching and experiencing alongside us. They hurt too. They are learning from the way their grownups navigate it all.

So let’s get honest.

No more saying ‘I’m good, thanks,” reflexively when I’m really not. Instead I say: I’m hurting inside or I feel unsafe or mothering is really challenging right now. Naming aloud exactly how I feel allows me to acknowledge that grief can be carried in its many iterations, forever. This is being human. It allows me to hold multiple truths at the same time: I may grieve and work, write, teach, cook, mother, call family, check on my community, and raise up those around me or do none of the above at all at this time. It doesn’t make me weak. Exactly the opposite: being honest means I am strong. This is what I want the children to see.

To honor the legacies of my people, I think about what made them especially powerful. Their imprints are enormous. Here’s where I landed. Afi and Uncle Hamid breathed pleasure. They relentlessly sought and cultivated pleasurable, healthy experiences for themselves and those around them, whether the smallest act in a delicious meal, a too-loud dance party, hearty hearty laughter or a walk near the water. We deny ourselves pleasurable experiences or even rest because we tell ourselves we have to earn it. For women of color especially, it even feels shameful to sit down. But we don’t earn these things. We all deserve it. I imagine sometimes that I too suddenly disappear in 20 some years, like these gorgeous people I love, like those bright souls in Uvalde, and ask myself: what pleasurable tiny rituals will I want to have savored?

Hold dear this continuum.

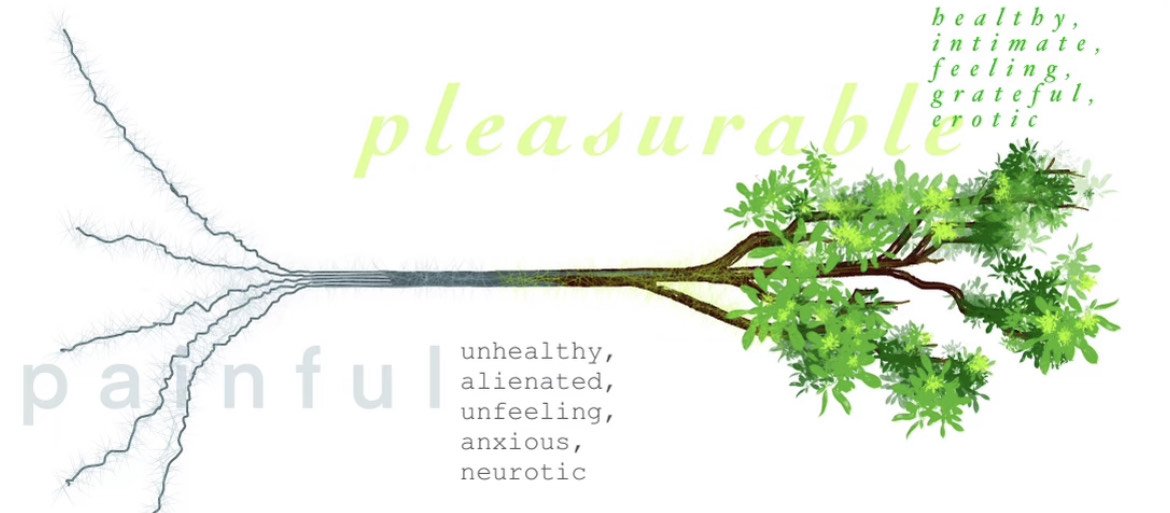

I envision a line labeled with pleasure, contentment, even eroticism on one end, with the other side marked by the neurotic, the dissatisfied, the robotic, unhealthy and unfeeling, a side I envision as fragmented cables gone haywire. And every morning when I wake up, I try my hardest to live on the emotive, feeling side. The side I imagine flourishes verdant, sprouting flowers and ferns. This humanness is about saying hello to any and all of those feelings. This is one way to heal. And it is an important part of grieving. As an educator, it helps me realize what is central to my teaching; what’s most important when I walk into classrooms, build relationships, and teach youth. As a mother, it reminds me of what I want my children to learn. Without this barometer for what actually matters in life, we lose touch with our humanity and the humanity of those around us. Our whole purpose of interconnectedness and collectivity disappears. We become cogs in an unfeeling machine; we adhere to baseless social constructs; we miss our connection to the earth and our people.

Without affording ourselves pleasure, we fail our children.

Created by my dear friend, Ryan Leigh Babbitt. Feel free to email [email protected] for a blank copy of your own.

Please, do this.

Create your own continuum. What are your pleasures, large and small? What intimacies can you ensure for yourself? What keeps you feeling wholly alive? For me, lighting tall taper candles at dinner is a small act of beautiful eroticism. Scratching the back of my toddler’s neck before bed while telling her stories about my parents in Iran keeps me feeling. You might get specific. And then ask yourself questions about the other end, too. When and what has made you feel neurotic and robotic and unhealthy?

Listen to me. It is untrue that grieving lasts just as long as narrowly defined bereavement leaves. That is external, arbitrary, societal pressure. And it is untrue that we cannot name truthfully how we feel while also being “professional.” Stomp those limited beliefs. Fortify yourselves. We can say we need a day just to savor the feel of water between our fingers. We can slow our breath outdoors. In fact, we have to. Our children are watching us.

Texts that shaped thinking around this piece:

Uncle Hamid’s life celebration playlist (music)

Crying in H Mart (memoir)

Rumi’s The Guest House (poem)

Braiding Sweetgrass (young readers version in the works)

The Bias of Professionalism Standards (article)

Pleasure Activism (nonfiction)

Nawal Qarooni is an educator, literacy coach and writer who supports a holistic literacy model of instruction in schools. She and her team of coaches at NQC Literacy work alongside teachers and school leaders to grow a love of reading and composition in ways that exalt the whole child, their cultural capital, and their intrinsic curiosities. She is the proud daughter of immigrants, and mothering her four young kids shapes her understanding of teaching and learning. Nawal’s first book with Heinemann about family and caregiver literacy is forthcoming in 2023. She is a graduate of the University of Michigan, Syracuse University’s Newhouse School of Journalism, and Brooklyn College. She transitioned from reporting to education via the New York City Teaching Fellows program. Listen to a recording or read her 2021 #31DaysIBPOC piece on the importance of the collective here.

This blog post is part of the #31DaysIBPOC Blog Series, a month-long movement to feature the voices of indigenous and teachers of color as writers and scholars. Please CLICK HERE to read yesterday’s blog post by Dr. Lois Marshall Barker (and be sure to check out the link at the end of each post to catch up on the rest of the blog series).