Yesterday when I called my mom to ask how my aunt was doing, though she was speaking Farsi, my mother talked of serjeri that didn’t take. When I translated a board book aloud the other day when reading to the kids, and couldn’t place the word for squirrel, I asked my mother and she said the animal was called, esquirrel.

Neither is true. Amal and sanjob are the words for surgery and squirrel, but my mother immigrated to Pittsburgh from Shiraz when she was a teenager, having left the beautiful Zagros mountainous backdrop and her siblings for an American education my Baba Ghambar so highly respected. Now she’s sixty and her language is as muddled as our identities.

Who would’ve thought my mother would have met another Iranian and fallen in love, clear across the world from where both were born and raised, in a stone student union building neither could have ever imagined from their Iranian childhoods among pomegranates and persimmons?

My parents were married in 1981 in my mother’s backyard in Shiraz, despite the backdrop of the Iran-Iraq war, which raged for eight years and permanently kept them from returning home. When my mother called her father to say she had met a man who wanted to come for khastegari, my grandfather lamented what sort of wedding they could even throw during the war. But marry they did; my mother in a white dress she sewed herself, decorated with a green lei of sorts that represented prosperity and growth in their new union together.

I’m lost in these thoughts this morning as I think about my own compartmentalized language practices, of how hard my parents worked to ensure I spoke Farsi fluently and could understand my grandparents, who spoke little to no English at all. I remember being embarrassed about my American accent when visiting my cousins in Iran, but my mother said she had dreams of her Americanized children, having grown up coveting all things America during the Shah regime.

My Farsi is good, but I can’t write or read it beyond a second grade level. In Pittsburgh where I grew up, our next door neighbors randomly ended up being Iranians. Khaleh Shahnaz was a teacher in Tehran so she would hold Sunday evening lessons for me and her young sons, guiding us through workbooks and the aleph behs of the Arabic alphabet. Ali would walk me across the front lawns of our townhouses to ensure I got home safely; I remember the dark skies and the pine needles under foot.

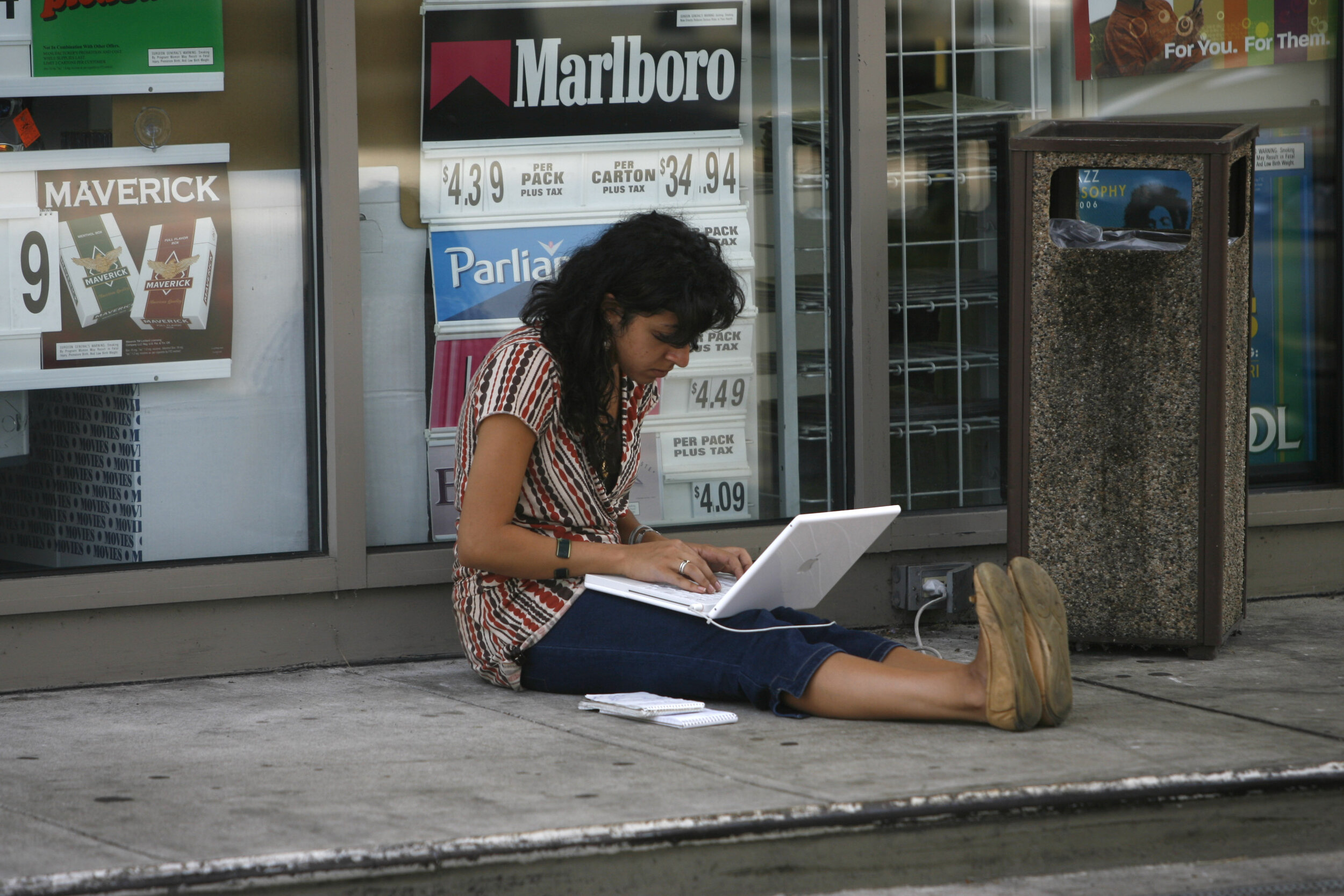

As a writer for the Star-Ledger, before my life in education, I reported out of Iran for several weeks. I stayed with my cousins but paid for a fixer and a driver who delivered me and an American photographer to government buildings when I was slated to interview then-President Ahmadinejad. I would ask questions in rapid Farsi and digest it all readily but scribble frantic notes in English and dump my thoughts into quick story form for wiring to the States in English, writing late into the night while my family was asleep to meet New Jersey deadlines. The disconnection between the boisterous, overly smiley photographer in my family’s homes, the stomping along the tiled walls of my grandparents’ backyard, the whispered long-distance calls to Jon, sitting at his desk in the newsroom in Newark, from my cousin Neda’s bedroom. It was all incongruous and disorienting.

Compartmentalization gone awry.

I’m contemplating liminality today. When I tell stories in Farsi, my words feel soft yet extreme, lyrical and unexpected. When I try translating them into English composition, the words are clunky and simple. How do immigrant children who straddle two worlds and multiple languages make meaning? How do multilingual children exalt their full repertoire of language practices and merge the intersections of who they are onto the page?

My mother is queen of translanguaging. When she tells stories, it is inevitable that we will hear accented English words seamlessly integrated into her Farsi, the result of decades spent between countries. This morning when I called to check on everyone and she saw Eloisa on Facetime, she said she couldn’t wait to see my nokhodchis, that she was ‘kheli exhausted.’ None of us fit into tidy little boxes with labels and definitions. Neither should our language and words.

Slice of Life, Day 27 – encouraged by Jennifer Mitchell to explore compartmentalized language practices, thank you

This is a slice of a life I have never lived. But I gulped every word of it. A favorite line about your mother: "her language is as muddled as our identities." We all combine words in unique ways, even when we have lived in the same place all our lives. I enjoyed reading about your family history, and the two cultures your family now has joined.

I was lost in your history, which made me think of my own. My mother is queen of translanguaging….our queen is my grandmother. Her Italian comes out even more now that she is 92.

I admire multilingual people, and your post makes me admire you and the rest of them even more. I love the reflections and some of the lines you have in this post. You’re creating a collection of such important insights, Nawal.

"When I tell stories in Farsi, my words feel soft yet extreme, lyrical and unexpected. When I try translating them into English composition, the words are clunky and simple. How do immigrant children who straddle two worlds and multiple languages make meaning? How do multilingual children exalt their full repertoire of language practices and merge the intersections of who they are onto the page?"

Such beautiful lines!

What a rich and multifaceted account of your family background and language observations! Thank you for sharing the pictures so generously with us. They complement your words in a way that feels intimate and welcoming. My favorite is the one of you on the sidewalk, laptop plugged in. To have served as a correspondent abroad! Wow!

I’m thinking too about my bilingual sons and our language habits; when we use which languages and with whom. Your post gives me lots to mull over.

I take this post to heart, now more than ever, as a native English speaker working on a dual language campus, with a lot of ESL students…and I am also a student of language, hundreds of days of practice in Spanish and Japanese, still barely able to understand or speak either. The students applaud my Spanish efforts (literally, they clap for me when I get a full sentence out). I have a truly bilingual daughter, and hope that she and her Japanese husband intend to rear their future children in a bilingual household. Maybe then, my Japanese will stick…

I have always believed that those with the most words have the most power, which means that multilingual learners such as you and your mom are forces to be reckoned with. Your inquiry into the thresholds of language made me ask big questions and consider how complex and beautiful translanguaging truly is. I recently had the privilege of hearing Ofelia García speak at a TCRWP Supper Club event, and so much of what you wrote about resonated with much of what I learned. She taught us that learners bring a symbiotic repertoire of experiences, culture, and languages to every text they read. Your beautiful blog captures this truth in extraordinary ways.

I love it when I stumble across a gem on Twitter!

I lived in Greece while I was in high school during the dictatorship of 1967. I was the only student in my British high school who was not Greek, yet spoke the language very well. In class we would speak a mixture of Greek and English that would move more toward Greek when we didn’t want the teacher to understand.

I also spent time in Italy eventually a year at University. My Italian wasn’t bad. I’ve studied French in school most of my life.

It is such a joy to by multi-lingual. I taught my children some French when they were little so they would have the experience of a second language. It is so sad when parents don’t teach their children their own native language.

Alas at 65 it is much more difficult to learn a new language now, or even more vocabulary in any language.

Paula Tusler @paulazt

I know you shared this piece with me because of the reporting/interviewing work, but I’m left thinking about my grandmother. She used to speak to my grandfather in Yiddish. She tried to teach it to me and I pushed back. To me, it was an old-world language. (My grandfather was an immigrant so perhaps that’s why I felt this way.) I didn’t want to learn it when I was a kid. What a stupid mistake I made. All I know now are little phrases and solitary words. I will never be fluent since I was a kid who pushed back on being multilingual since the language my grandparents spoke didn’t feel modern to me.